What am I going to tell my students?

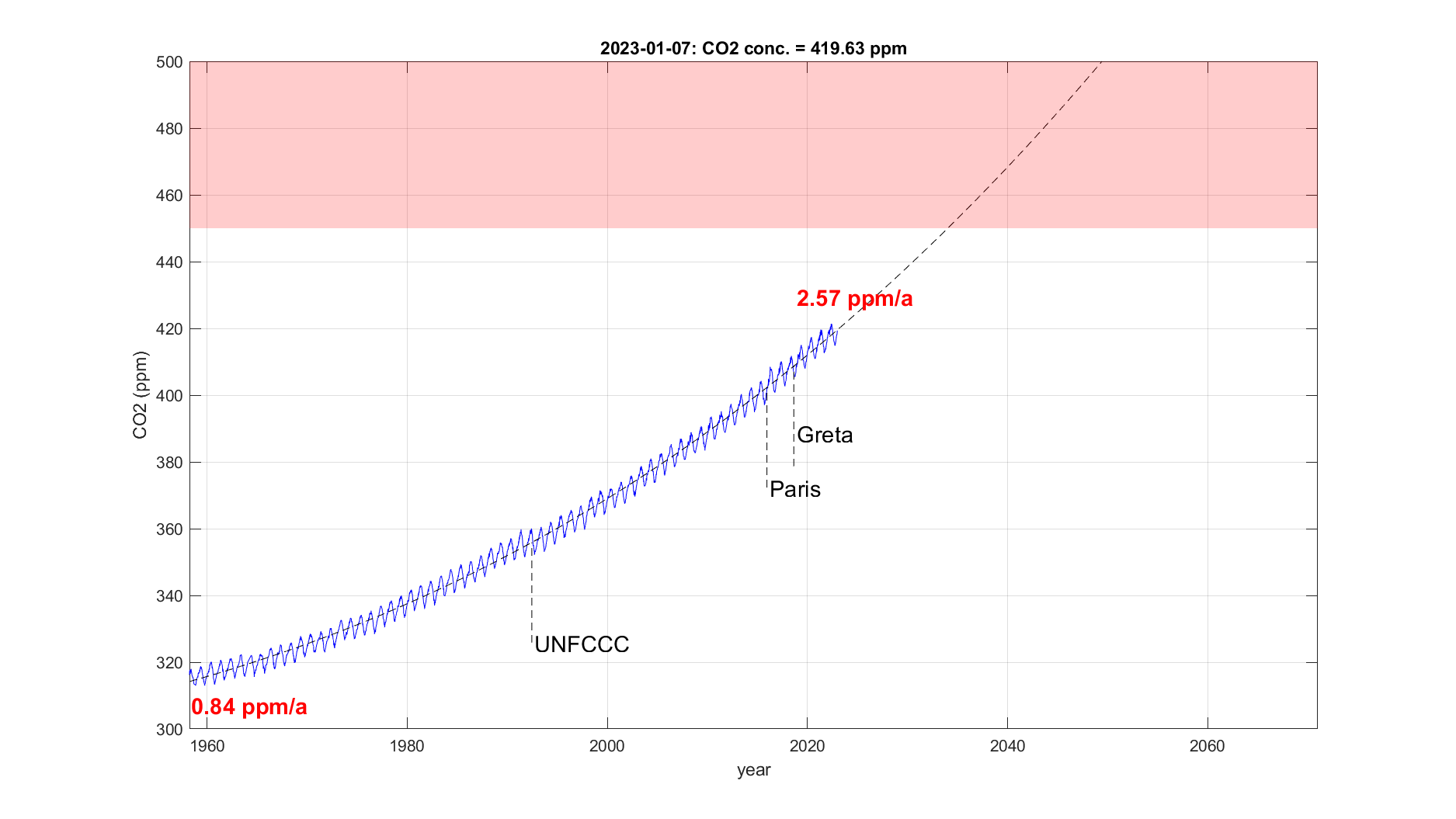

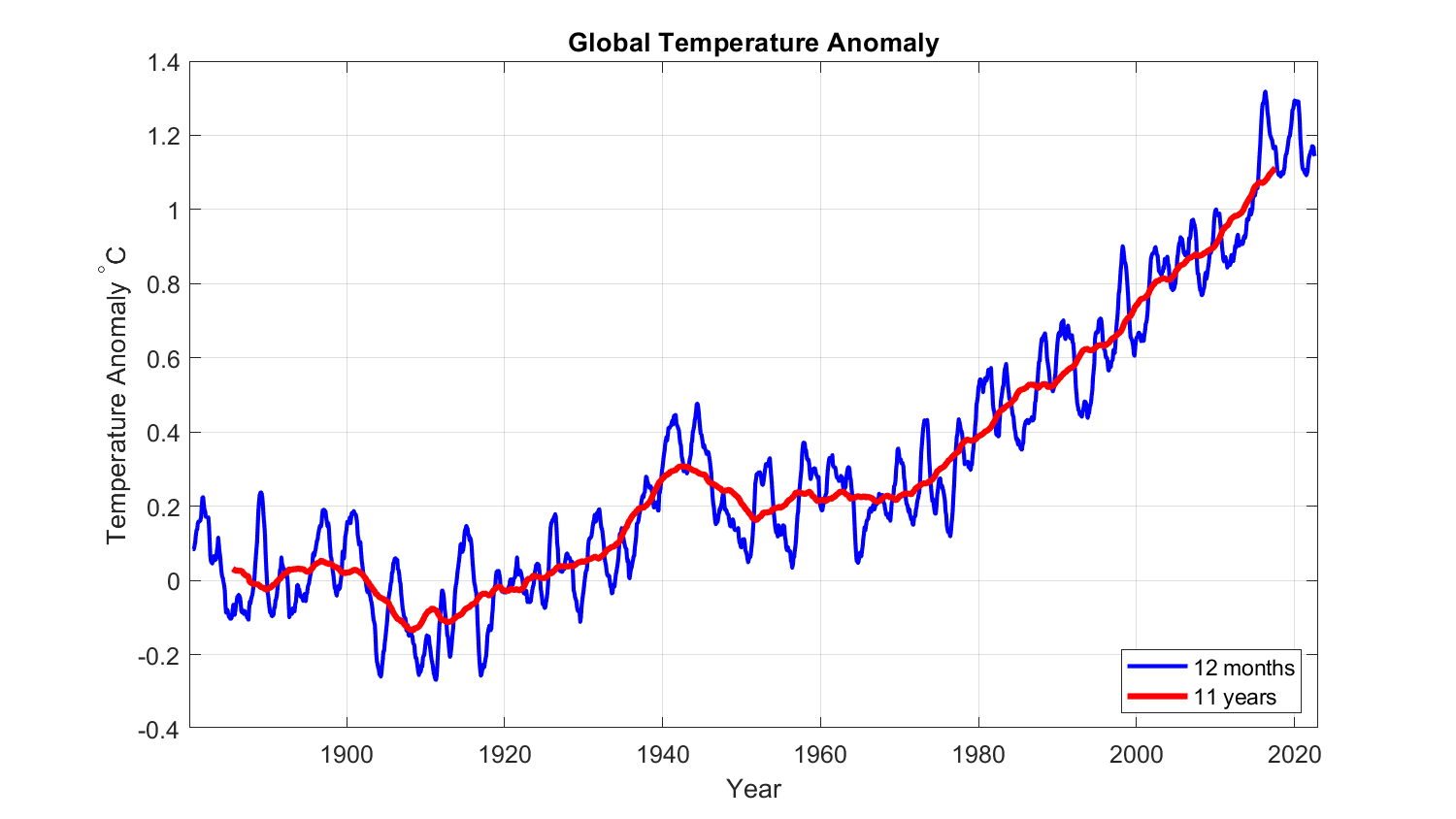

Many years ago, I read an illuminating prediction for the future. The author was a German engineer who had written about the automation and simplification of household appliances sometime during the late 50s or early 60s. With great enthusiasm, he described how technical improvements to dishwashers, stoves, and laundromats would make life simpler and concluded with a sentence that I will never forget: "The housewives of the future will only have to press a couple of buttons."Apparently, the thought of women having better things to do than washing or cooking or that men might help with household chores was beyond his imagination. There is no indication that he was trying to be funny, but his idea of innovation was strictly limited to technology. When trying to "think outside the box," he was immediately trapped in a slightly larger box. I am often reminded of this story when attending sustainability conferences sponsored by the private sector. They typically begin with a high-profile keynote speaker raving about how there is no contradiction between getting rich and saving the planet and how sustainable solutions can be profitable. This is when you know that the conference will ignore 99% of all effective climate solutions and only deal with the 1% compatible with current business models. Or, to put it differently, the focus of the conference will be to maintain capitalism rather than to save humanity. Thanks for reading Global Climate Compensation! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work. Climate destruction represents an unprecedented threat to the survival of human civilization and the most significant challenge our societies have ever faced. And yet, most people seem to assume that we will be able to fix the problem without essentially changing anything. This is incredibly frustrating. Shareholder capitalism requires corporations to focus on short-term profits, even when this harms their business in the long run. Science has become so specialized and competitive that researchers are writing papers rather than thinking about the real challenges facing humanity. In particular, no scientist dares to point out the obvious: innovations take decades to be turned into viable solutions that can be efficiently mass-produced. New technologies will have essentially zero impact on the level of carbon emissions in 2030. If we want to survive, we will have to make do with the tools we have and consume less. There is no realistic alternative to Degrowth. This is why I am delighted that we managed to convince Rachel Donald to give a talk during the Sustainability Week at our university. For over two years, she has been doing what many business leaders, politicians, and scientists did not: asking the right questions. Rather than starting from a fixed set of ideas, she has invited a wide range of people – scientists, philosophers, economists, climate activists, and authors – and asked them about the state of the world and possible solutions. In doing so, she has developed a keen sense of what is rotten in the state of the world. The planetary crisis poses a unique challenge to educational institutions, as the teachers are perhaps more clueless than the students about how to respond. Furthermore, the students are the ones whose lives will be impacted. The least we can do as teachers is to be open to their demands and show that we care. And I do care. Consider the two diagrams below. The first shows the carbon concentration in the atmosphere. It has increased by roughly 50% since the beginning of the industrial revolution – every third CO2 molecule is now of anthropogenic origin – and is rising faster than ever. This decade will decide whether it will be possible to limit global warming to less than +2.0°C, and things do not look good. The second plot shows the global temperature anomaly. The Earth has already warmed by roughly 1.2°C, and the temperature is increasing by more than +0.2°C per decade. This is approximately 100 times faster than before the industrial revolution. This semester, I will be lecturing in front of more than 100 students. Most of them are in their early to mid 20s, meaning they can expect to live for another six decades. Many children in the world today will still be alive in the year 2100. Try extrapolating the temperature curve above another 80 years into the future. How am I supposed to explain this to my students? On March 22, Rachel will be joined by Graeme Maxton, Irmi Seidel, Rolf Wüstenhagen, and Elimar Frank in what I hope will be an open, frank, and lively debate on the future of human civilization. Audience participation will be strongly encouraged. If you are in the Zurich area, this will be an excellent opportunity to connect, discuss, and share ideas. Registration and further information can be found here: Planet Critical live at OST. BTW, the CO2 and temperature plots are based on publicly available data and were generated using Matlab. I would be happy to send the code if anyone is interested. Otherwise, the sources are here: Global Climate Compensation is free today. But if you enjoyed this post, you can tell Global Climate Compensation that their writing is valuable by pledging a future subscription. You won't be charged unless they enable payments.

Read Global Climate Compensation in the app Listen to posts, join subscriber chats, and never miss an update from Henrik Nordborg. © 2023 Henrik Nordborg |